Thompson (cited in Rantanen 2005, p. 5) defined globalisation as ‘the growing interconnectedness of different parts of the world, a process which gives rise to complex forms of interaction and interdependency’. Examining the definition, he emphasized the ‘interactivity’ of globalisation, which means interchange between nations. When it comes to the media, cultural products such as films can be exchanged easily across geographical borders thanks to globalisation (Croteau et al. 2012, p. 327). As Waters (cited in Rantanen 2005, p. 5) argues, culture is an expression of symbols representing values, meanings, beliefs and preferences. In this context, the globalisation of media involves both positives and negatives. It is up to how well the cultural products interact in different countries. This paper examines the negative consequences of globalisation, especially cultural imperialism through the screening of Hollywood movies. The paper also discusses a protective film policy in Korea for the purpose of safeguarding its film industries and maintaining Korean culture.

Nowadays, U.S. culture such as American television programs, films, and music are common in other countries across the world (Croteau et al. 2012, p. 333). Film and television are regarded as American ‘soft power’ embodying in the American way of life (De Zoysa, R, & Newman 2002, p. 189). Lee (2005, p. 1) describes films as ‘the main vehicle for cultural expression’. This means films have an important role in helping promote cultural identities (Lee 2005, p. 1). In many countries, increasing U.S. dominance has brought about the decline of domestic film industries. It is considered as a threat to cultural sovereignty and domestic film industries (Lee & Bae 2004, p. 163).

Nowadays, U.S. culture such as American television programs, films, and music are common in other countries across the world (Croteau et al. 2012, p. 333). Film and television are regarded as American ‘soft power’ embodying in the American way of life (De Zoysa, R, & Newman 2002, p. 189). Lee (2005, p. 1) describes films as ‘the main vehicle for cultural expression’. This means films have an important role in helping promote cultural identities (Lee 2005, p. 1). In many countries, increasing U.S. dominance has brought about the decline of domestic film industries. It is considered as a threat to cultural sovereignty and domestic film industries (Lee & Bae 2004, p. 163). When it comes to film exports, Hollywood films account for 85% of the world market in general (UNESCO 2000). Specifically, according to EurAcitv (cited in Croteau et al. 2012, p. 333), European Union movie theatres were dominated by American movies attracting over 67% of European audiences in 2009. In contrast, according to European Audiovisual Observatory European (cited in Croteau et al. 2012, p. 333), European films accounted for less than 7% of the North American film market share in 2010. Moreover, U.S. films have a worldwide share of 90% in many countries including Canada, Australia, Norway, Switzerland, Belgium, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Indonesia, Taiwan (Lee 2005, p. 1). These statistics definitely show American ‘soft power’.

When it comes to film exports, Hollywood films account for 85% of the world market in general (UNESCO 2000). Specifically, according to EurAcitv (cited in Croteau et al. 2012, p. 333), European Union movie theatres were dominated by American movies attracting over 67% of European audiences in 2009. In contrast, according to European Audiovisual Observatory European (cited in Croteau et al. 2012, p. 333), European films accounted for less than 7% of the North American film market share in 2010. Moreover, U.S. films have a worldwide share of 90% in many countries including Canada, Australia, Norway, Switzerland, Belgium, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Indonesia, Taiwan (Lee 2005, p. 1). These statistics definitely show American ‘soft power’.

Some people argue that increasing US dominance for a number of years has led to a form of cultural imperialism. Tunstall (cited in Tomlinson 2002, p. 8) describes cultural imperialism as large quantities of commercial and media products, mainly form the United States that have contributed to a decline of traditional and local cultures in many parts of the world. Western media products have contributed to the spread of its values and the habits of its culture (Tomlinson 2002, p. 3). For instance, values of individualism and consumerism are resent in western cultural products (Croteau et al. 2012, p. 333). Anti-cultural imperialists worry that these western media products result in the decline of local cultures, sometimes even clashing with traditional values (Croteau et al. 2012, p. 333). China’s film industry during the 1930s and the 1940s can be seen an example of the cultural imperialism of Hollywood movies. From 1919 to 1949, Hollywood films had an effect on the Chinese film industry directly (Su 2011, p. 196). During the 1930s and the 1940s, Hollywood films were a symbol of ‘modernity’ including the American lifestyle (Su 2011, p. 196). U.S cultural values clashed with traditional Chinese ethical and moral standards and consequently traditional Chinese values were undermined by Hollywood films (Su 2011, p. 196).

Under such circumstances, in order to protect their own culture and domestic film industries, countries impose many protective film policies such as subsidies, import quotas, screen quotas and television quotas (Cheng et al. 2010, p. 270). Specifically, 15 countries adopt screen quota systems, including 7 countries in Asia (Korea, India, China, Egypt, Pakistan, Indonesia, Sri Lanka), 5 countries in South America (Brazil, Mexico, Columbia, Argentina, Venezuela) and 3 countries in Europe (Greece, Spain, France) (Cheng et al. 2010, p. 270; Lee 2005, p. 8).

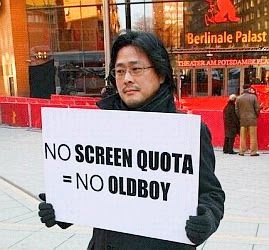

A screen quota system is ‘a governmental regulation that makes it compulsory for movie theatres to screen the feature films of national origin for a specified period of time’ (Lee & Bae 2004, p. 164). Korea reduced its minimum screening days from 146 days to 73 days in a year because the U.S pushed the Korean government to remove this system (Lee & Bae 2004, p. 164; John 2002). There were disputes in Korea as to whether ‘the screen quota system’ should be reduced, if not completely removed a few years ago (Seo 2005, p. 1). Advocates of the screen quota emphasize cultural diversity, cultural exceptions and national identity (Seo 2005, p. 1). They argue that this system effectively protects the Korean film industry and the diversity of films from the flood of Hollywood movies (Seo 2005, p. 2). On the other hand, opponents of the screen quota contend that the screen quota system is against the principle of free trade and limits domestic consumers’ choices (Seo 2005, p. 2).

Even though screen quotas were first introduced to Korea in 1966, this system did not play any significant role in protecting Korea’s film industries until 1993 (Lee & Bae 2004, p. 165). This is because the government controlled the Korean film market (Lee 2005, p. 17). In order to enforce the system effectively, screen quota watchers were created and started to keep an eye on the minimum quota requirement in 1993 (Lee 2005, p. 17). The screen quota system operated effectively from this year. This is because when movie theatres did not keep the exact days, violators were punished by the penal regulation (Lee 2005, p. 19). As movie theatres kept a minimum screening period, for the first time, the number of domestic film exhibition days (111 days) reached the minimum quota requirement (106 days) in 1998 (Lee 2005, p. 19).

In respect of the diversity of films, Korean audiences can watch diverse films thanks to the enforcement of the screen quota system. With the opening of the Korean film market in 1987, U.S. films’ market share increased from 45%-50% to 75% (1997-1998) at its highest (Lee 2005, p. 24). Then it decreased to the level of 45% -50% until 2002 (Lee 2005, p. 24). Today, despite recent US pressure, the share of Korean films being shared in Korea is over 50%. According to CDMI report (cited in Lee 2005, p. 24), in order to enhance the screen quota system, the Korean film community is calling for the introduction of Art Film Screen Quota, including Third world films to proceed even further diversity.

In conclusion, this paper has explored the negative consequences of globalisation, especially cultural imperialism through the screening of Hollywood movies. It has suggested that films have a significant role in helping promote cultural identities and argues that in many countries, increasing U.S. dominance brings about the decline of domestic film industries. The paper also has discussed the protective film policy in Korea to safeguard its film industries and the examination has found that the Korean screen quota system has played an important role in promoting and preserving the Korean film industry.

Bibliography

Cheng, H, Feng, J, Koehler, G, & Marston, S 2010, 'Entertainment without borders: the impact of digital technologies on government cultural policy', Journal Of Management Information Systems, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 269-302, retrieved 4 October 2012, Business Source Complete, EBSCOhost.

Croteau, D, Hoynes, W, Milan, S 2012, Media/society: industries, images, and audiences, SAGE, California.

De Zoysa, R, & Newman, O 2002, 'Globalization, soft power and the challenge of Hollywood', Contemporary Politics, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 185-202, retrieved 23 September 2012, Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost.

John, P 2012 ‘What is the future of Korean film?’, The Korea Herald, 17 September, retrieved 4 October 2012, <http://khnews.kheraldm.com/kh/view.php?ud=20120917000815&md=20120917204211_C>.

Lee ,B & Bae, H 2004, 'The effect of screen quotas on the self-sufficiency ratio in recent domestic film markets', Journal Of Media Economics, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 163-176, retrieved 4 October 2012, Business Source Complete, EBSCOhost.

Lee, H 2005, 'An economic analysis of protective film policies: acase study of the Korean screen quota system', Conference Papers -- International Communication Association, pp. 1-38, retrieved 20 September 2012, Communication & Mass Media Complete, EBSCOhost.

Rantanen, T 2005, The media and globalization, Sage, London.

Seo, Y 2005, 'The Politics of the 'Screen Quota System' in Korea: art, culture, and film in the age of global capitalism', Conference Papers -- American Political Science Association, pp. 1-24, retrieved 30 July 2012, Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost.

Su, W 2011, 'Resisting cultural imperialism, or welcoming cultural globalization? China's extensive debate on Hollywood cinema from 1994 to 2007', Asian Journal Of Communication, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 186-201, retrieved 23 September 2012, Communication & Mass Media Complete, EBSCOhost.

Tomlinson, J 2002, Cultural imperialism: a critical introduction, Continuum, retrieved 4 October 2012, <http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=acls;idno=heb02149>.

UNESCO 2000, ‘In brief’, UNESCO Sources, Vol. 124, pp. 16, retrieved 30 September 2012, Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost, <http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001228/122897eo.pdf>

Picture sources

http://internationalpoliticsclass.wordpress.com/

http://koreanpopculture.blogspot.com.au/2006/02/no-screen-quota-no-oldboy.html

https://wikis.nyu.edu/ek6/modernamerica/index.php/Imperialism/CulturalImperialism

http://www.phpbbplanet.com/professionalgol/viewtopic.php?t=927&sid=b4ff16820c6b611e5547dd474fc84746&mforum=professionalgol

http://www.anomalousmaterial.com/movies/2010/03/the-cost-of-making-a-hollywood-movie/